Quiz-summary

0 of 30 questions completed

Questions:

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

Information

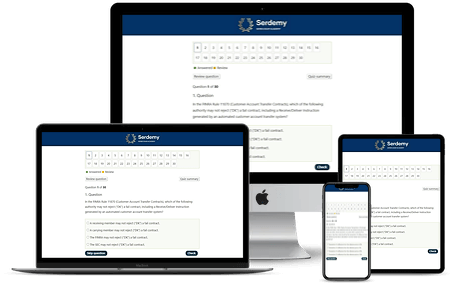

Premium Practice Questions

You have already completed the quiz before. Hence you can not start it again.

Quiz is loading...

You must sign in or sign up to start the quiz.

You have to finish following quiz, to start this quiz:

Results

0 of 30 questions answered correctly

Your time:

Time has elapsed

Categories

- Not categorized 0%

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- Answered

- Review

-

Question 1 of 30

1. Question

Alistair, an investment adviser representative and designated “access person” at Keystone Wealth Managers, a federal covered adviser, engaged in several personal securities activities during the third quarter. He purchased shares in a new technology IPO, bought several U.S. Treasury bonds, acquired additional shares of an unaffiliated open-end mutual fund, and had dividends automatically reinvested in a blue-chip stock he holds in his personal account. According to the reporting requirements under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which of these activities must Alistair include on his quarterly transaction report to Keystone’s Chief Compliance Officer?

Correct

The conclusion is that only the purchase of the technology IPO shares must be reported. This is determined by applying the specific requirements of Rule 204A-1 under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, also known as the Code of Ethics Rule. This rule mandates that “access persons” of an investment adviser report their personal securities transactions to the firm’s Chief Compliance Officer on a quarterly basis. However, the rule provides several important exemptions for what constitutes a “reportable security” and a “reportable transaction.” First, we analyze the purchase of U.S. Treasury bonds. Securities that are direct obligations of the Government of the United States are explicitly excluded from the definition of a “reportable security.” Therefore, any transaction in these instruments does not need to be included in the quarterly transaction report. Second, we consider the acquisition of shares in an unaffiliated open-end mutual fund. The rule specifically exempts transactions and holdings in shares of open-end mutual funds from the quarterly transaction reporting requirement, provided the adviser does not serve as the investment adviser or principal underwriter for the fund. It is important to distinguish this from the initial and annual holdings reports, where such funds typically must be disclosed. Third, the automatic reinvestment of dividends falls under the exemption for acquisitions of securities through an automatic investment plan. In such plans, subsequent investments are made automatically based on a pre-set schedule or trigger, and the access person does not direct each individual transaction. This makes the acquisition non-reportable on the quarterly transaction report. Finally, the purchase of shares in an Initial Public Offering (IPO) involves a “reportable security,” as common stock does not fall under any exemption. The transaction is a voluntary purchase directed by the access person and is not part of an automatic plan. Therefore, this transaction must be reported on the quarterly transaction report. In fact, most firm’s codes of ethics have stricter pre-clearance requirements for IPOs and limited offerings.

Incorrect

The conclusion is that only the purchase of the technology IPO shares must be reported. This is determined by applying the specific requirements of Rule 204A-1 under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, also known as the Code of Ethics Rule. This rule mandates that “access persons” of an investment adviser report their personal securities transactions to the firm’s Chief Compliance Officer on a quarterly basis. However, the rule provides several important exemptions for what constitutes a “reportable security” and a “reportable transaction.” First, we analyze the purchase of U.S. Treasury bonds. Securities that are direct obligations of the Government of the United States are explicitly excluded from the definition of a “reportable security.” Therefore, any transaction in these instruments does not need to be included in the quarterly transaction report. Second, we consider the acquisition of shares in an unaffiliated open-end mutual fund. The rule specifically exempts transactions and holdings in shares of open-end mutual funds from the quarterly transaction reporting requirement, provided the adviser does not serve as the investment adviser or principal underwriter for the fund. It is important to distinguish this from the initial and annual holdings reports, where such funds typically must be disclosed. Third, the automatic reinvestment of dividends falls under the exemption for acquisitions of securities through an automatic investment plan. In such plans, subsequent investments are made automatically based on a pre-set schedule or trigger, and the access person does not direct each individual transaction. This makes the acquisition non-reportable on the quarterly transaction report. Finally, the purchase of shares in an Initial Public Offering (IPO) involves a “reportable security,” as common stock does not fall under any exemption. The transaction is a voluntary purchase directed by the access person and is not part of an automatic plan. Therefore, this transaction must be reported on the quarterly transaction report. In fact, most firm’s codes of ethics have stricter pre-clearance requirements for IPOs and limited offerings.

-

Question 2 of 30

2. Question

Leo, an Investment Adviser Representative, is dining at an exclusive restaurant where he overhears the Chief Financial Officer of AeroDyne Innovations Inc., a publicly traded biotech firm, telling a companion that the company’s flagship drug has just failed its final-stage clinical trial and that this devastating news will be announced publicly the next morning. Leo’s client, Ms. Anya Sharma, holds a substantial position in AeroDyne. Leo immediately calls Ms. Sharma and strongly advises her to liquidate her entire position, which she does, thereby avoiding a significant loss. Which of the following best describes why Leo’s action is a prohibited practice under the Uniform Securities Act?

Correct

The core issue is the use of material, non-public information (MNPI) for securities trading. Insider trading laws, including provisions under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the Insider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act of 1988 (ITSFEA), prohibit such activities. Information is considered material if a reasonable investor would likely consider it important in making an investment decision. The impending failure of a key clinical trial for a company’s main product is unequivocally material. The information is non-public because it has not been disseminated to the general marketplace. An investment adviser representative has a fiduciary duty to their clients, but this duty does not permit or require them to violate federal or state securities laws. The prohibition against insider trading supersedes the duty to act in a client’s best interest if doing so involves using MNPI. The violation occurs when a person trades, or causes others to trade, while in possession of MNPI. It is not necessary for the adviser to personally profit from the transaction. Advising a client to trade based on this information is a direct violation. The manner in which the information was obtained, whether through a direct tip or by accidentally overhearing it, does not absolve the individual from the responsibility to refrain from trading on it if they know or should have known it was MNPI. The representative’s action of advising the client to sell constitutes a prohibited use of inside information.

Incorrect

The core issue is the use of material, non-public information (MNPI) for securities trading. Insider trading laws, including provisions under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the Insider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act of 1988 (ITSFEA), prohibit such activities. Information is considered material if a reasonable investor would likely consider it important in making an investment decision. The impending failure of a key clinical trial for a company’s main product is unequivocally material. The information is non-public because it has not been disseminated to the general marketplace. An investment adviser representative has a fiduciary duty to their clients, but this duty does not permit or require them to violate federal or state securities laws. The prohibition against insider trading supersedes the duty to act in a client’s best interest if doing so involves using MNPI. The violation occurs when a person trades, or causes others to trade, while in possession of MNPI. It is not necessary for the adviser to personally profit from the transaction. Advising a client to trade based on this information is a direct violation. The manner in which the information was obtained, whether through a direct tip or by accidentally overhearing it, does not absolve the individual from the responsibility to refrain from trading on it if they know or should have known it was MNPI. The representative’s action of advising the client to sell constitutes a prohibited use of inside information.

-

Question 3 of 30

3. Question

Mei is an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) for a federal covered investment adviser, Apex Wealth Managers. Through Apex’s internal, non-public research portal, she learns that the firm’s analysts are building a strong case for recommending “Innovatech Corp.,” a small-cap technology firm, to clients in the coming weeks. Before Apex issues any recommendations, Mei uses her personal brokerage account, held at an unaffiliated firm, to purchase a significant block of Innovatech shares. She subsequently writes a general article for her personal financial blog about growth prospects in the small-cap tech sector, without mentioning Innovatech specifically. She properly includes the Innovatech purchase on her next required quarterly transaction report to Apex’s Chief Compliance Officer. Which of Mei’s actions represents the most significant breach of her fiduciary duty?

Correct

The core issue revolves around the fiduciary duty an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) owes to their clients and their employing firm. This duty requires the IAR to place client interests ahead of their own. The most significant violation is the act of trading for one’s personal account based on confidential information obtained through their employment before the firm or its clients have the opportunity to act on that information. This practice is known as front-running. Even though the information is the firm’s internal research and not necessarily material non-public information from a corporate insider, it is still privileged information. Using it for personal gain creates a direct conflict of interest. The Investment Advisers Act of 1940, through Rule 204A-1 (the Code of Ethics Rule), requires advisers to adopt codes of ethics to prevent such activities. The rule mandates that “access persons” (which includes most IARs) report their personal securities transactions and holdings. However, reporting a prohibited transaction after the fact does not cure the underlying ethical and legal breach. The violation is the act of self-dealing and prioritizing personal profit over client interests. While other actions, such as engaging in outside business activities like blogging or maintaining outside brokerage accounts, also have compliance requirements like disclosure and approval, they are secondary to the act of front-running, which is a fundamental breach of the adviser’s fiduciary obligation.

Incorrect

The core issue revolves around the fiduciary duty an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) owes to their clients and their employing firm. This duty requires the IAR to place client interests ahead of their own. The most significant violation is the act of trading for one’s personal account based on confidential information obtained through their employment before the firm or its clients have the opportunity to act on that information. This practice is known as front-running. Even though the information is the firm’s internal research and not necessarily material non-public information from a corporate insider, it is still privileged information. Using it for personal gain creates a direct conflict of interest. The Investment Advisers Act of 1940, through Rule 204A-1 (the Code of Ethics Rule), requires advisers to adopt codes of ethics to prevent such activities. The rule mandates that “access persons” (which includes most IARs) report their personal securities transactions and holdings. However, reporting a prohibited transaction after the fact does not cure the underlying ethical and legal breach. The violation is the act of self-dealing and prioritizing personal profit over client interests. While other actions, such as engaging in outside business activities like blogging or maintaining outside brokerage accounts, also have compliance requirements like disclosure and approval, they are secondary to the act of front-running, which is a fundamental breach of the adviser’s fiduciary obligation.

-

Question 4 of 30

4. Question

Kenji is a data analyst at a federally covered investment adviser. While not an IAR, his role grants him access to nonpublic information regarding upcoming portfolio rebalancing for the firm’s major institutional clients, making him an “access person”. The firm’s Code of Ethics mirrors the requirements of Rule 204A-1 under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Which of the following actions by Kenji would represent a violation of his personal securities reporting obligations under the rule?

Correct

Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, Rule 204A-1, also known as the Code of Ethics Rule, requires registered investment advisers to adopt and enforce a code of ethics. A central component of this rule involves personal securities transaction reporting by certain employees defined as access persons. An access person is generally any supervised person of the adviser who has access to nonpublic information regarding clients’ securities transactions, who is involved in making securities recommendations to clients, or who has access to such recommendations that are nonpublic. The rule mandates three types of reports from access persons. First, an initial holdings report listing all reportable securities is due no later than 10 days after the person becomes an access person. Second, an annual holdings report is required at least once every 12 months thereafter. For both initial and annual reports, the information must be current as of a date no more than 45 days before the report is submitted. Third, and most relevant to this scenario, is the quarterly transaction report. An access person must submit a report of all personal transactions in reportable securities within 30 days of the end of each calendar quarter. A critical detail of this requirement is that the report must be submitted even if the access person had no transactions in reportable securities during that quarter. In such a case, the access person would submit a report indicating that no transactions were effected. Failing to submit this “negative” or “no activity” report is a violation of the rule. Certain securities, such as direct obligations of the U.S. government, money market instruments, and shares of open-end mutual funds (unless the adviser serves as the fund’s adviser or underwriter), are typically exempt from these reporting requirements.

Incorrect

Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, Rule 204A-1, also known as the Code of Ethics Rule, requires registered investment advisers to adopt and enforce a code of ethics. A central component of this rule involves personal securities transaction reporting by certain employees defined as access persons. An access person is generally any supervised person of the adviser who has access to nonpublic information regarding clients’ securities transactions, who is involved in making securities recommendations to clients, or who has access to such recommendations that are nonpublic. The rule mandates three types of reports from access persons. First, an initial holdings report listing all reportable securities is due no later than 10 days after the person becomes an access person. Second, an annual holdings report is required at least once every 12 months thereafter. For both initial and annual reports, the information must be current as of a date no more than 45 days before the report is submitted. Third, and most relevant to this scenario, is the quarterly transaction report. An access person must submit a report of all personal transactions in reportable securities within 30 days of the end of each calendar quarter. A critical detail of this requirement is that the report must be submitted even if the access person had no transactions in reportable securities during that quarter. In such a case, the access person would submit a report indicating that no transactions were effected. Failing to submit this “negative” or “no activity” report is a violation of the rule. Certain securities, such as direct obligations of the U.S. government, money market instruments, and shares of open-end mutual funds (unless the adviser serves as the fund’s adviser or underwriter), are typically exempt from these reporting requirements.

-

Question 5 of 30

5. Question

Assessment of the situation of Amara, an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) at a state-registered advisory firm, reveals a potential conflict of interest. After conducting extensive independent research, she has identified a micro-cap security she believes has significant upside potential. She plans to recommend this security to several of her suitable clients and also wishes to purchase a substantial position for her own personal account. To comply with her fiduciary duty and the firm’s Code of Ethics, which of the following actions is the most critical and immediate step the firm’s Chief Compliance Officer must ensure is taken?

Correct

No calculation is required for this question. The core principle at issue is the fiduciary duty an investment adviser owes to its clients, which is the highest standard of care in equity or law. This duty requires the adviser and its representatives to act solely in the best interests of their clients, placing client interests ahead of their own. A significant part of this duty involves identifying, disclosing, and managing conflicts of interest. When an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) intends to trade a security for their personal account that they are also recommending to clients, a clear conflict of interest arises. The potential for the IAR to benefit at the expense of clients, for instance through front-running, is a major regulatory concern. Front-running is the prohibited practice of entering a personal order ahead of a client’s order to profit from the market movement the client’s larger order might cause. Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and the Uniform Securities Act, registered investment advisers must adopt and enforce a Code of Ethics (Rule 204A-1). This code must, among other things, establish procedures for “access persons” (which includes most IARs) to report their personal securities transactions and holdings. Crucially, it must also require pre-clearance for certain personal investments to prevent conflicts. However, simply pre-clearing a trade is not enough. To fully adhere to the fiduciary standard, the firm’s procedures must ensure that clients are not disadvantaged by the IAR’s personal trading. This means client orders must be given priority, and clients must receive executions at prices that are at least as favorable as, if not more favorable than, the price the IAR receives. The firm must have a concrete process to ensure client trades are executed first or that the IAR’s trade is part of a block trade where all parties receive an average price, thus preventing any preferential treatment for the IAR.

Incorrect

No calculation is required for this question. The core principle at issue is the fiduciary duty an investment adviser owes to its clients, which is the highest standard of care in equity or law. This duty requires the adviser and its representatives to act solely in the best interests of their clients, placing client interests ahead of their own. A significant part of this duty involves identifying, disclosing, and managing conflicts of interest. When an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) intends to trade a security for their personal account that they are also recommending to clients, a clear conflict of interest arises. The potential for the IAR to benefit at the expense of clients, for instance through front-running, is a major regulatory concern. Front-running is the prohibited practice of entering a personal order ahead of a client’s order to profit from the market movement the client’s larger order might cause. Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and the Uniform Securities Act, registered investment advisers must adopt and enforce a Code of Ethics (Rule 204A-1). This code must, among other things, establish procedures for “access persons” (which includes most IARs) to report their personal securities transactions and holdings. Crucially, it must also require pre-clearance for certain personal investments to prevent conflicts. However, simply pre-clearing a trade is not enough. To fully adhere to the fiduciary standard, the firm’s procedures must ensure that clients are not disadvantaged by the IAR’s personal trading. This means client orders must be given priority, and clients must receive executions at prices that are at least as favorable as, if not more favorable than, the price the IAR receives. The firm must have a concrete process to ensure client trades are executed first or that the IAR’s trade is part of a block trade where all parties receive an average price, thus preventing any preferential treatment for the IAR.

-

Question 6 of 30

6. Question

Assessment of an IAR’s compliance with personal trading regulations reveals a specific sequence of events. Anika, an IAR at Apex Wealth Managers, a federal covered adviser, maintains a personal securities account at an unaffiliated brokerage firm. On April 10th, she purchases shares of a small-cap technology stock for her personal account. On April 25th, Apex Wealth Managers’ research department initiates coverage and issues a “buy” recommendation for the same stock, and Anika subsequently begins recommending it to her advisory clients. Under the provisions of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 concerning personal securities transactions, which of the following accurately describes Anika’s primary compliance obligation regarding this specific trade?

Correct

Calculation: Transaction Date: April 10th End of Calendar Quarter containing the transaction: June 30th (End of Q2) Reporting Deadline: No later than 30 days after the end of the quarter. Deadline = June 30th + 30 days = July 30th. Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, Rule 204A-1, commonly known as the Code of Ethics Rule, imposes specific personal trading reporting requirements on certain individuals associated with an investment adviser. These individuals are referred to as access persons. An Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) is considered an access person. The rule mandates that every access person must submit personal securities transaction reports to the adviser’s Chief Compliance Officer or another designated person. These reports must be submitted on a quarterly basis. The deadline for submitting the quarterly transaction report is no later than 30 days after the end of each calendar quarter. In the given scenario, the transaction occurred on April 10th, which falls within the second calendar quarter (April 1 to June 30). Therefore, the transaction must be included in the report for the second quarter. This report must be submitted to the firm no later than 30 days after June 30th. It is important to distinguish this requirement from a firm’s internal pre-clearance procedures, which may also be required by the firm’s code of ethics but represent a separate obligation. The fundamental regulatory reporting requirement is tied to the end of the quarter, not the specific trade date or the date of a subsequent firm recommendation.

Incorrect

Calculation: Transaction Date: April 10th End of Calendar Quarter containing the transaction: June 30th (End of Q2) Reporting Deadline: No later than 30 days after the end of the quarter. Deadline = June 30th + 30 days = July 30th. Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, Rule 204A-1, commonly known as the Code of Ethics Rule, imposes specific personal trading reporting requirements on certain individuals associated with an investment adviser. These individuals are referred to as access persons. An Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) is considered an access person. The rule mandates that every access person must submit personal securities transaction reports to the adviser’s Chief Compliance Officer or another designated person. These reports must be submitted on a quarterly basis. The deadline for submitting the quarterly transaction report is no later than 30 days after the end of each calendar quarter. In the given scenario, the transaction occurred on April 10th, which falls within the second calendar quarter (April 1 to June 30). Therefore, the transaction must be included in the report for the second quarter. This report must be submitted to the firm no later than 30 days after June 30th. It is important to distinguish this requirement from a firm’s internal pre-clearance procedures, which may also be required by the firm’s code of ethics but represent a separate obligation. The fundamental regulatory reporting requirement is tied to the end of the quarter, not the specific trade date or the date of a subsequent firm recommendation.

-

Question 7 of 30

7. Question

Anika, an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) with a federal covered adviser, is proposing a new portfolio management arrangement to Mr. Chen, a client who meets the definition of a “qualified client.” The proposal includes a fulcrum fee, where the advisory fee will increase or decrease based on the portfolio’s performance against the S&P 500 Index. Additionally, Anika’s firm has a soft-dollar arrangement with its primary broker-dealer, through which it receives third-party research reports and analytical software in exchange for directing a certain volume of client trades. An assessment of this arrangement reveals several compliance considerations. For this entire arrangement to be compliant with the adviser’s fiduciary duty, which of the following is the most complete and accurate description of the disclosures Anika must provide to Mr. Chen?

Correct

The core of this scenario involves the intersection of two complex regulatory areas for an investment adviser: performance-based fees and soft-dollar arrangements. Both are permissible under specific conditions but are fraught with potential conflicts of interest that trigger significant disclosure obligations under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. First, performance-based fees, such as the fulcrum fee described, are generally prohibited. However, an exception exists under Rule 205-3 for contracts with “qualified clients.” A qualified client is a person or company that has at least $1.1 million in assets under management with the adviser or has a net worth which the adviser reasonably believes to be in excess of $2.2 million. When such a fee is used, the adviser must disclose the fee formula, the period over which performance is measured, the benchmark index used, the risks of such a fee arrangement (including the incentive to take greater risks), and that the fee may create a conflict of interest. Second, soft-dollar arrangements are governed by the safe harbor of Section 28(e) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. This allows an adviser to use client commissions to pay for brokerage and research services. To qualify for the safe harbor, the adviser must determine in good faith that the commission amount is reasonable in relation to the value of the brokerage and research services received. The research must provide lawful and appropriate assistance to the adviser in the performance of their investment decision-making responsibilities. A significant conflict of interest arises because the adviser may be incentivized to direct trades to a broker-dealer providing research rather than to one that offers the best execution at the lowest cost. Therefore, the adviser’s fiduciary duty requires a full and fair disclosure of all material facts and conflicts. In this combined scenario, it is not enough to disclose the details of the performance fee or the existence of the soft-dollar arrangement in isolation. The adviser must provide a comprehensive disclosure that explains both arrangements and, critically, the potential conflicts of interest they create. This includes disclosing that the soft-dollar arrangement may result in clients paying higher commissions than they might otherwise pay and that the adviser has a conflict in seeking best execution.

Incorrect

The core of this scenario involves the intersection of two complex regulatory areas for an investment adviser: performance-based fees and soft-dollar arrangements. Both are permissible under specific conditions but are fraught with potential conflicts of interest that trigger significant disclosure obligations under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. First, performance-based fees, such as the fulcrum fee described, are generally prohibited. However, an exception exists under Rule 205-3 for contracts with “qualified clients.” A qualified client is a person or company that has at least $1.1 million in assets under management with the adviser or has a net worth which the adviser reasonably believes to be in excess of $2.2 million. When such a fee is used, the adviser must disclose the fee formula, the period over which performance is measured, the benchmark index used, the risks of such a fee arrangement (including the incentive to take greater risks), and that the fee may create a conflict of interest. Second, soft-dollar arrangements are governed by the safe harbor of Section 28(e) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. This allows an adviser to use client commissions to pay for brokerage and research services. To qualify for the safe harbor, the adviser must determine in good faith that the commission amount is reasonable in relation to the value of the brokerage and research services received. The research must provide lawful and appropriate assistance to the adviser in the performance of their investment decision-making responsibilities. A significant conflict of interest arises because the adviser may be incentivized to direct trades to a broker-dealer providing research rather than to one that offers the best execution at the lowest cost. Therefore, the adviser’s fiduciary duty requires a full and fair disclosure of all material facts and conflicts. In this combined scenario, it is not enough to disclose the details of the performance fee or the existence of the soft-dollar arrangement in isolation. The adviser must provide a comprehensive disclosure that explains both arrangements and, critically, the potential conflicts of interest they create. This includes disclosing that the soft-dollar arrangement may result in clients paying higher commissions than they might otherwise pay and that the adviser has a conflict in seeking best execution.

-

Question 8 of 30

8. Question

An investment adviser representative, Kenji, is conducting a two-year performance review for his client, Anika. Anika’s account started with $500,000. After the first year, the account value had fallen to $450,000. At the beginning of the second year, Anika made an additional contribution of $500,000. At the end of the second year, the account’s total value was $1,235,000. To accurately evaluate his own investment management effectiveness, independent of the timing of Anika’s large contribution, what is the annualized time-weighted return Kenji should present for the two-year period?

Correct

The calculation for the time-weighted annualized return (TWR) requires determining the holding period return for each period and then geometrically linking them. The TWR isolates the performance of the investment manager by removing the effects of the timing and size of cash flows. First, calculate the holding period return (HPR) for Year 1. Initial Value (Time 0) = $500,000 Value at End of Year 1 (Time 1) = $450,000 \[HPR_1 = \frac{\text{Ending Value}}{\text{Beginning Value}} – 1 = \frac{\$450,000}{\$500,000} – 1 = 0.90 – 1 = -0.10 \text{ or } -10.0\%\] Next, calculate the holding period return (HPR) for Year 2. The beginning value for this period must include the new cash flow. Beginning Value for Year 2 (after contribution) = $450,000 (value from Year 1) + $500,000 (new contribution) = $950,000 Ending Value for Year 2 (Time 2) = $1,235,000 \[HPR_2 = \frac{\text{Ending Value}}{\text{Beginning Value}} – 1 = \frac{\$1,235,000}{\$950,000} – 1 = 1.30 – 1 = 0.30 \text{ or } +30.0\%\] Finally, calculate the annualized time-weighted return by finding the geometric mean of the two holding period returns. \[TWR = \left[ (1 + HPR_1) \times (1 + HPR_2) \right]^{\frac{1}{n}} – 1\] \[TWR = \left[ (1 – 0.10) \times (1 + 0.30) \right]^{\frac{1}{2}} – 1\] \[TWR = \left[ (0.90) \times (1.30) \right]^{\frac{1}{2}} – 1\] \[TWR = \left[ 1.17 \right]^{0.5} – 1\] \[TWR = 1.081665 – 1 = 0.081665\] The annualized time-weighted return is approximately 8.17%. This method provides the compound rate of growth of one dollar invested in the portfolio over the measurement period. It is the industry standard for evaluating a portfolio manager’s performance because it is not influenced by client decisions regarding the timing of investments or withdrawals. In contrast, a dollar-weighted return, or internal rate of return, measures the actual return earned by the client’s money and is heavily influenced by cash flow timing. A manager whose portfolio performs well after a large client contribution will have a high dollar-weighted return, which reflects the client’s fortunate timing as much as the manager’s skill. Therefore, to purely assess the manager’s investment selection and timing decisions, the time-weighted return is the appropriate metric. The arithmetic average of the returns is a less accurate method as it ignores the effects of compounding over time.

Incorrect

The calculation for the time-weighted annualized return (TWR) requires determining the holding period return for each period and then geometrically linking them. The TWR isolates the performance of the investment manager by removing the effects of the timing and size of cash flows. First, calculate the holding period return (HPR) for Year 1. Initial Value (Time 0) = $500,000 Value at End of Year 1 (Time 1) = $450,000 \[HPR_1 = \frac{\text{Ending Value}}{\text{Beginning Value}} – 1 = \frac{\$450,000}{\$500,000} – 1 = 0.90 – 1 = -0.10 \text{ or } -10.0\%\] Next, calculate the holding period return (HPR) for Year 2. The beginning value for this period must include the new cash flow. Beginning Value for Year 2 (after contribution) = $450,000 (value from Year 1) + $500,000 (new contribution) = $950,000 Ending Value for Year 2 (Time 2) = $1,235,000 \[HPR_2 = \frac{\text{Ending Value}}{\text{Beginning Value}} – 1 = \frac{\$1,235,000}{\$950,000} – 1 = 1.30 – 1 = 0.30 \text{ or } +30.0\%\] Finally, calculate the annualized time-weighted return by finding the geometric mean of the two holding period returns. \[TWR = \left[ (1 + HPR_1) \times (1 + HPR_2) \right]^{\frac{1}{n}} – 1\] \[TWR = \left[ (1 – 0.10) \times (1 + 0.30) \right]^{\frac{1}{2}} – 1\] \[TWR = \left[ (0.90) \times (1.30) \right]^{\frac{1}{2}} – 1\] \[TWR = \left[ 1.17 \right]^{0.5} – 1\] \[TWR = 1.081665 – 1 = 0.081665\] The annualized time-weighted return is approximately 8.17%. This method provides the compound rate of growth of one dollar invested in the portfolio over the measurement period. It is the industry standard for evaluating a portfolio manager’s performance because it is not influenced by client decisions regarding the timing of investments or withdrawals. In contrast, a dollar-weighted return, or internal rate of return, measures the actual return earned by the client’s money and is heavily influenced by cash flow timing. A manager whose portfolio performs well after a large client contribution will have a high dollar-weighted return, which reflects the client’s fortunate timing as much as the manager’s skill. Therefore, to purely assess the manager’s investment selection and timing decisions, the time-weighted return is the appropriate metric. The arithmetic average of the returns is a less accurate method as it ignores the effects of compounding over time.

-

Question 9 of 30

9. Question

Consider a scenario where Kenji, an investment adviser representative for Apex Wealth Managers, a federal covered adviser based in California, makes a personal political contribution of $250 to the campaign of a candidate running for state treasurer in Nevada. The Nevada state treasurer has direct influence over the selection of investment managers for the state’s employee retirement fund. Kenji is a resident of California. One year after Kenji’s contribution, Apex Wealth Managers is selected to manage a portion of the Nevada state employee retirement fund. According to the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, what are the consequences of this situation?

Correct

The situation described is governed by SEC Rule 206(4)-5, commonly known as the “pay-to-play” rule, under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. This rule is designed to prevent investment advisers from improperly influencing the award of advisory contracts by making political contributions to government officials who can influence such decisions. The rule applies to registered investment advisers, exempt reporting advisers, and their “covered associates.” A covered associate includes any partner, executive officer, or employee of the adviser who solicits a government entity for advisory business. In this scenario, Kenji is a covered associate. The core of the rule prohibits an investment adviser from providing advisory services for compensation to a government entity for a period of two years after the adviser or any of its covered associates makes a contribution to an official of that government entity. However, the rule provides for de minimis exceptions. A covered associate can contribute up to $350 per election to an official for whom they are entitled to vote. For contributions to officials for whom the covered associate is not entitled to vote, the de minimis limit is reduced to $150 per election. In this case, Kenji is a resident of California and is making a contribution to a candidate for office in Nevada. Therefore, he is not entitled to vote for that official. The applicable de minimis limit is $150. Kenji’s contribution of $250 exceeds this limit. As a result of this contribution, Kenji’s firm, Apex Wealth Managers, is triggered into the two-year “time out” period. The firm is prohibited from receiving any compensation, including advisory fees, from the Nevada state employee retirement fund for two years, measured from the date Kenji made the contribution. The prohibition applies to the entire firm, not just the individual who made the contribution.

Incorrect

The situation described is governed by SEC Rule 206(4)-5, commonly known as the “pay-to-play” rule, under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. This rule is designed to prevent investment advisers from improperly influencing the award of advisory contracts by making political contributions to government officials who can influence such decisions. The rule applies to registered investment advisers, exempt reporting advisers, and their “covered associates.” A covered associate includes any partner, executive officer, or employee of the adviser who solicits a government entity for advisory business. In this scenario, Kenji is a covered associate. The core of the rule prohibits an investment adviser from providing advisory services for compensation to a government entity for a period of two years after the adviser or any of its covered associates makes a contribution to an official of that government entity. However, the rule provides for de minimis exceptions. A covered associate can contribute up to $350 per election to an official for whom they are entitled to vote. For contributions to officials for whom the covered associate is not entitled to vote, the de minimis limit is reduced to $150 per election. In this case, Kenji is a resident of California and is making a contribution to a candidate for office in Nevada. Therefore, he is not entitled to vote for that official. The applicable de minimis limit is $150. Kenji’s contribution of $250 exceeds this limit. As a result of this contribution, Kenji’s firm, Apex Wealth Managers, is triggered into the two-year “time out” period. The firm is prohibited from receiving any compensation, including advisory fees, from the Nevada state employee retirement fund for two years, measured from the date Kenji made the contribution. The prohibition applies to the entire firm, not just the individual who made the contribution.

-

Question 10 of 30

10. Question

An evaluation of an IAR’s conduct with an ERISA-governed plan reveals a potential violation. Anika, an IAR, advises Mateo, the trustee of his company’s 401(k) plan, to allocate a portion of the plan’s assets into a private real estate investment fund. Anika’s advisory firm is a significant general partner in this same real estate fund and will receive management fees from it. Assuming no specific prohibited transaction exemption applies, which statement most accurately describes the primary fiduciary breach under ERISA?

Correct

The core issue in this scenario is the violation of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) rules regarding prohibited transactions. ERISA Section 406 establishes strict prohibitions to prevent conflicts of interest and self-dealing by plan fiduciaries and parties in interest. A “party in interest” includes any fiduciary, a person providing services to the plan (like an investment adviser), and an employer whose employees are covered by the plan. In this case, the investment adviser representative (IAR) is a plan fiduciary, and her firm, which provides advisory services, is a party in interest. The IAR’s recommendation causes the 401(k) plan to invest its assets in a fund where her own firm is a general partner and stands to gain financially through management fees. This is a classic example of self-dealing. ERISA Section 406(b) specifically prohibits a fiduciary from dealing with the assets of the plan in their own interest or for their own account. The fiduciary is using her position to generate business and fees for her firm, which is a direct conflict with her duty to act solely in the interest of the plan participants and beneficiaries. It does not matter if the investment is potentially profitable or if the conflict is disclosed to the plan trustee. Under ERISA’s strict liability standard for prohibited transactions, the act itself is a violation, unless a specific statutory or administrative exemption is granted, which was not indicated in the scenario.

Incorrect

The core issue in this scenario is the violation of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) rules regarding prohibited transactions. ERISA Section 406 establishes strict prohibitions to prevent conflicts of interest and self-dealing by plan fiduciaries and parties in interest. A “party in interest” includes any fiduciary, a person providing services to the plan (like an investment adviser), and an employer whose employees are covered by the plan. In this case, the investment adviser representative (IAR) is a plan fiduciary, and her firm, which provides advisory services, is a party in interest. The IAR’s recommendation causes the 401(k) plan to invest its assets in a fund where her own firm is a general partner and stands to gain financially through management fees. This is a classic example of self-dealing. ERISA Section 406(b) specifically prohibits a fiduciary from dealing with the assets of the plan in their own interest or for their own account. The fiduciary is using her position to generate business and fees for her firm, which is a direct conflict with her duty to act solely in the interest of the plan participants and beneficiaries. It does not matter if the investment is potentially profitable or if the conflict is disclosed to the plan trustee. Under ERISA’s strict liability standard for prohibited transactions, the act itself is a violation, unless a specific statutory or administrative exemption is granted, which was not indicated in the scenario.

-

Question 11 of 30

11. Question

Leo, an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR), manages a Uniform Transfers to Minors Act (UTMA) account for which Priya is the custodian. Impressed with the account’s significant growth, Priya proposes a new compensation structure in a signed letter: for the next calendar year, Leo will receive 30% of all realized capital gains but must personally reimburse the account for 30% of all realized capital losses. From the perspective of the Uniform Securities Act, what is the status of this proposed arrangement?

Correct

Under the Uniform Securities Act, it is an unethical business practice for an investment adviser representative to share, directly or indirectly, in the profits or losses of any client account. This prohibition is a cornerstone of fiduciary duty, designed to prevent conflicts of interest that could encourage an IAR to take excessive risks with a client’s capital. Unlike the rule for agents of broker-dealers, there is no exception for IARs that would permit such an arrangement, even with the client’s written consent and the firm’s approval. The client’s willingness to enter into the agreement and provide it in writing does not override the state securities Administrator’s rules. While performance-based fee arrangements are permitted for certain qualified clients under specific conditions, they are structured differently and do not involve the IAR covering a percentage of the account’s losses. The proposed arrangement is a direct sharing of both profits and losses, which is a clear violation of the ethical standards applicable to IARs. Therefore, the IAR must refuse the client’s offer, as accepting it would subject the IAR to disciplinary action by the Administrator. The nature of the account, in this case a UTMA, further complicates the matter from the custodian’s perspective, but the fundamental prohibition rests on the IAR’s conduct regardless of the account type.

Incorrect

Under the Uniform Securities Act, it is an unethical business practice for an investment adviser representative to share, directly or indirectly, in the profits or losses of any client account. This prohibition is a cornerstone of fiduciary duty, designed to prevent conflicts of interest that could encourage an IAR to take excessive risks with a client’s capital. Unlike the rule for agents of broker-dealers, there is no exception for IARs that would permit such an arrangement, even with the client’s written consent and the firm’s approval. The client’s willingness to enter into the agreement and provide it in writing does not override the state securities Administrator’s rules. While performance-based fee arrangements are permitted for certain qualified clients under specific conditions, they are structured differently and do not involve the IAR covering a percentage of the account’s losses. The proposed arrangement is a direct sharing of both profits and losses, which is a clear violation of the ethical standards applicable to IARs. Therefore, the IAR must refuse the client’s offer, as accepting it would subject the IAR to disciplinary action by the Administrator. The nature of the account, in this case a UTMA, further complicates the matter from the custodian’s perspective, but the fundamental prohibition rests on the IAR’s conduct regardless of the account type.

-

Question 12 of 30

12. Question

The following case involves Pinnacle Wealth Managers, a federal covered investment adviser that has a long-standing advisory contract with a state’s public pension fund. Leo, an Investment Adviser Representative and covered associate at Pinnacle, resides in the state and is eligible to vote in its elections. He makes a personal contribution of $500 to the re-election campaign of the incumbent state treasurer, an official who has influence over the selection of investment advisers for the pension fund. What is the most direct regulatory consequence for Pinnacle Wealth Managers as a result of Leo’s action?

Correct

The scenario involves SEC Rule 206(4)-5, commonly known as the “pay-to-play” rule. This rule is designed to prevent investment advisers from making political contributions to government officials in exchange for being awarded advisory contracts with government entities. Under this rule, if an investment adviser or any of its “covered associates” makes a contribution to an official of a government entity, the adviser is prohibited from providing advisory services for compensation to that government entity for a two-year period following the contribution. A “covered associate” includes any general partner, managing member, executive officer, or other individual with a similar status or function; any employee who solicits a government entity for the adviser; and any person who supervises such an employee. In this case, Leo, as an Investment Adviser Representative of Pinnacle, is a covered associate. The state treasurer is an official of a government entity, and the state’s pension fund is that government entity. The rule has de minimis exceptions. A covered associate can contribute up to $350 per election to an official for whom they are entitled to vote, and up to $150 per election to an official for whom they are not entitled to vote, without triggering the two-year ban. Leo’s contribution of $500 exceeds the $350 de minimis threshold. Therefore, this contribution is a violation of the rule. The direct consequence for Pinnacle Wealth Managers is a two-year “time out” during which it cannot receive compensation for its advisory services from the state’s pension fund. The prohibition is on receiving compensation, not necessarily on providing services, and it lasts for two years from the date of the contribution.

Incorrect

The scenario involves SEC Rule 206(4)-5, commonly known as the “pay-to-play” rule. This rule is designed to prevent investment advisers from making political contributions to government officials in exchange for being awarded advisory contracts with government entities. Under this rule, if an investment adviser or any of its “covered associates” makes a contribution to an official of a government entity, the adviser is prohibited from providing advisory services for compensation to that government entity for a two-year period following the contribution. A “covered associate” includes any general partner, managing member, executive officer, or other individual with a similar status or function; any employee who solicits a government entity for the adviser; and any person who supervises such an employee. In this case, Leo, as an Investment Adviser Representative of Pinnacle, is a covered associate. The state treasurer is an official of a government entity, and the state’s pension fund is that government entity. The rule has de minimis exceptions. A covered associate can contribute up to $350 per election to an official for whom they are entitled to vote, and up to $150 per election to an official for whom they are not entitled to vote, without triggering the two-year ban. Leo’s contribution of $500 exceeds the $350 de minimis threshold. Therefore, this contribution is a violation of the rule. The direct consequence for Pinnacle Wealth Managers is a two-year “time out” during which it cannot receive compensation for its advisory services from the state’s pension fund. The prohibition is on receiving compensation, not necessarily on providing services, and it lasts for two years from the date of the contribution.

-

Question 13 of 30

13. Question

An Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) at a state-registered firm, Keystone Advisory, purchases 500 shares of a thinly-traded technology company for her personal account. One week later, Keystone’s research department, unaware of the IAR’s personal trade, initiates coverage on the company with a strong “buy” rating. The IAR, citing the firm’s new research, immediately recommends the stock to several of her suitable clients, who subsequently purchase it. Under the Uniform Securities Act and associated ethical guidelines, which of the following represents the most significant breach of fiduciary duty committed by the IAR?

Correct

The central issue in this scenario is the conflict of interest that arises from the Investment Adviser Representative’s personal trading activity relative to their recommendations to clients. The IAR’s fiduciary duty, a cornerstone of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and the Uniform Securities Act, mandates that the adviser must always act in the best interests of their clients and place the clients’ interests ahead of their own. Purchasing a security for a personal account shortly before recommending that same security to advisory clients constitutes a significant breach of this duty. This practice, often referred to as trading ahead of clients, allows the IAR to potentially profit from the market activity generated by their own recommendations. Even if the IAR’s purchase did not influence the subsequent research report, the act of recommending the stock to clients after establishing a personal position creates an undeniable conflict of interest. The proper course of action would have been to disclose the personal holding to the clients before or at the time of the recommendation, or to abstain from making the recommendation altogether. While reporting personal securities transactions is a separate compliance requirement, the act of trading ahead of clients is a more fundamental ethical and fiduciary violation. It is distinct from insider trading, which requires the use of material non-public information, and from selling away, which involves transactions outside the firm’s purview. The primary failure is the subordination of client interests to the representative’s personal financial interests.

Incorrect

The central issue in this scenario is the conflict of interest that arises from the Investment Adviser Representative’s personal trading activity relative to their recommendations to clients. The IAR’s fiduciary duty, a cornerstone of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 and the Uniform Securities Act, mandates that the adviser must always act in the best interests of their clients and place the clients’ interests ahead of their own. Purchasing a security for a personal account shortly before recommending that same security to advisory clients constitutes a significant breach of this duty. This practice, often referred to as trading ahead of clients, allows the IAR to potentially profit from the market activity generated by their own recommendations. Even if the IAR’s purchase did not influence the subsequent research report, the act of recommending the stock to clients after establishing a personal position creates an undeniable conflict of interest. The proper course of action would have been to disclose the personal holding to the clients before or at the time of the recommendation, or to abstain from making the recommendation altogether. While reporting personal securities transactions is a separate compliance requirement, the act of trading ahead of clients is a more fundamental ethical and fiduciary violation. It is distinct from insider trading, which requires the use of material non-public information, and from selling away, which involves transactions outside the firm’s purview. The primary failure is the subordination of client interests to the representative’s personal financial interests.

-

Question 14 of 30

14. Question

An assessment of the trading activity of Mateo, an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) for a federal covered adviser, reveals a particular pattern. On several occasions, Mateo has identified thinly-traded securities for potential inclusion in client portfolios. In each instance, he purchased shares for his own account and then, within the same trading day, distributed a research report and recommendation to the firm’s clients. The subsequent influx of client orders consistently drove the share price higher. Which of the following most accurately describes the regulatory consequence of Mateo’s trading pattern?

Correct

Aggregate client disadvantage calculation: Initial price per share: \(\$35.00\) Price after IAR’s purchase and recommendation dissemination: \(\$36.25\) Price increase per share: \(\$36.25 – \$35.00 = \$1.25\) Total shares purchased by clients: \(20,000\) Aggregate additional cost to clients: \(20,000 \text{ shares} \times \$1.25/\text{share} = \$25,000\) This calculation demonstrates the tangible financial harm to clients resulting from the investment adviser representative’s actions. The practice of an adviser personally trading on material, non-public information about their own forthcoming recommendations is known as front-running. It is a serious breach of the fiduciary duty owed to clients. This duty requires an adviser to always place client interests ahead of their own. By purchasing securities for a personal account immediately before issuing a widespread buy recommendation that is likely to increase the price, the adviser is leveraging their position for personal gain at the direct expense of their clients, who are forced to pay a higher price. This activity is a prohibited and unethical business practice under both the Uniform Securities Act and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. It is considered a manipulative and fraudulent act. Investment advisers must establish, maintain, and enforce a written code of ethics that includes provisions to prevent such conflicts of interest. These provisions often include blackout periods, which prohibit personal trading around the time of client recommendations, or require that client orders receive priority execution. The violation occurs at the time of the trade, regardless of whether a profit is ultimately realized or how long the position is held.

Incorrect

Aggregate client disadvantage calculation: Initial price per share: \(\$35.00\) Price after IAR’s purchase and recommendation dissemination: \(\$36.25\) Price increase per share: \(\$36.25 – \$35.00 = \$1.25\) Total shares purchased by clients: \(20,000\) Aggregate additional cost to clients: \(20,000 \text{ shares} \times \$1.25/\text{share} = \$25,000\) This calculation demonstrates the tangible financial harm to clients resulting from the investment adviser representative’s actions. The practice of an adviser personally trading on material, non-public information about their own forthcoming recommendations is known as front-running. It is a serious breach of the fiduciary duty owed to clients. This duty requires an adviser to always place client interests ahead of their own. By purchasing securities for a personal account immediately before issuing a widespread buy recommendation that is likely to increase the price, the adviser is leveraging their position for personal gain at the direct expense of their clients, who are forced to pay a higher price. This activity is a prohibited and unethical business practice under both the Uniform Securities Act and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. It is considered a manipulative and fraudulent act. Investment advisers must establish, maintain, and enforce a written code of ethics that includes provisions to prevent such conflicts of interest. These provisions often include blackout periods, which prohibit personal trading around the time of client recommendations, or require that client orders receive priority execution. The violation occurs at the time of the trade, regardless of whether a profit is ultimately realized or how long the position is held.

-

Question 15 of 30

15. Question

Assessment of an IAR’s compliance obligations reveals a potential reporting requirement. Anika, an investment adviser representative and designated “access person” at a state-registered advisory firm, learns on May 15th that she has inherited a portfolio of securities from a deceased relative. The portfolio consists of common stock in a publicly traded technology company, shares of a non-affiliated open-end mutual fund, and several U.S. Treasury bonds. According to the ethical obligations and reporting requirements for access persons under the Uniform Securities Act, which action must Anika take regarding this inheritance?

Correct

The calculation determines the deadline for an access person to report a securities transaction. If an access person becomes aware of an involuntary acquisition, such as an inheritance, on May 15th, this event occurs in the second calendar quarter (Q2), which ends on June 30th. The rule requires the transaction to be reported no later than 30 days after the end of the quarter in which the transaction occurred. End of Quarter Date = June 30 Reporting Deadline = End of Quarter Date + 30 days \[ \text{June 30} + 30 \text{ days} = \text{July 30} \] Therefore, the report is due by July 30th. Under the Uniform Securities Act and principles aligned with the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, investment advisory firms must have a code of ethics to prevent fraudulent and unethical practices. This code applies to certain employees defined as access persons. An access person typically includes any supervised person who has access to nonpublic information regarding clients’ securities transactions, who is involved in making securities recommendations to clients, or who has access to such recommendations that are nonpublic. These individuals have specific reporting obligations. They must submit quarterly transaction reports for any transaction in a reportable security in which they have, or as a result of the transaction acquire, any direct or indirect beneficial ownership. An acquisition through an involuntary event like an inheritance is a reportable transaction. However, not all securities are reportable. The definition of a reportable security explicitly excludes direct obligations of the U.S. Government, money market instruments, and shares of open-end mutual funds, provided the adviser does not serve as the investment adviser or principal underwriter for the fund. Therefore, only the transactions in securities that do not meet these exemptions must be included in the quarterly report, which is due within 30 days of the end of the calendar quarter.

Incorrect

The calculation determines the deadline for an access person to report a securities transaction. If an access person becomes aware of an involuntary acquisition, such as an inheritance, on May 15th, this event occurs in the second calendar quarter (Q2), which ends on June 30th. The rule requires the transaction to be reported no later than 30 days after the end of the quarter in which the transaction occurred. End of Quarter Date = June 30 Reporting Deadline = End of Quarter Date + 30 days \[ \text{June 30} + 30 \text{ days} = \text{July 30} \] Therefore, the report is due by July 30th. Under the Uniform Securities Act and principles aligned with the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, investment advisory firms must have a code of ethics to prevent fraudulent and unethical practices. This code applies to certain employees defined as access persons. An access person typically includes any supervised person who has access to nonpublic information regarding clients’ securities transactions, who is involved in making securities recommendations to clients, or who has access to such recommendations that are nonpublic. These individuals have specific reporting obligations. They must submit quarterly transaction reports for any transaction in a reportable security in which they have, or as a result of the transaction acquire, any direct or indirect beneficial ownership. An acquisition through an involuntary event like an inheritance is a reportable transaction. However, not all securities are reportable. The definition of a reportable security explicitly excludes direct obligations of the U.S. Government, money market instruments, and shares of open-end mutual funds, provided the adviser does not serve as the investment adviser or principal underwriter for the fund. Therefore, only the transactions in securities that do not meet these exemptions must be included in the quarterly report, which is due within 30 days of the end of the calendar quarter.

-

Question 16 of 30

16. Question

Kenji, an Investment Adviser Representative and a designated “access person” at a large federal covered investment adviser, is reviewing his personal investment strategy. He identifies a publicly-traded software company he believes is undervalued and wishes to purchase 500 shares for his own account. The adviser’s research department has recently issued a “buy” recommendation for the same security to its clients. To remain in compliance with the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, what is the most critical obligation Kenji must fulfill regarding this personal transaction?

Correct

The situation described involves an “access person” of an investment adviser engaging in a personal securities transaction. Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, specifically Rule 204A-1, registered investment advisers are required to adopt and enforce a code of ethics to prevent fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative practices. This rule is designed to manage conflicts of interest that arise when advisory personnel trade for their own accounts. A key component of the code of ethics is the requirement for access persons to report their personal securities transactions and holdings. An access person generally includes any supervised person who has access to nonpublic information regarding client transactions or portfolio holdings, or who is involved in making securities recommendations to clients. The rule mandates that access persons submit quarterly transaction reports, typically within 30 days of the end of each calendar quarter. These reports must detail all personal securities transactions during that period. While the rule itself explicitly requires pre-clearance only for investments in initial public offerings (IPOs) and limited offerings, it also obligates the adviser’s code of ethics to establish procedures for managing personal trading. In practice, to manage the conflict of interest when an access person trades a security that the firm is also recommending to clients, most firms implement a mandatory pre-clearance policy for all or a significant subset of personal trades. This is considered a best practice and is the primary mechanism by which a firm ensures that client interests are placed first. Therefore, the access person’s immediate responsibility is to adhere to the firm’s specific procedures outlined in its code of ethics, which almost certainly includes a pre-clearance requirement for this type of transaction. Following this internal procedure is the first step before the subsequent regulatory requirement of reporting the transaction on the quarterly report.

Incorrect

The situation described involves an “access person” of an investment adviser engaging in a personal securities transaction. Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, specifically Rule 204A-1, registered investment advisers are required to adopt and enforce a code of ethics to prevent fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative practices. This rule is designed to manage conflicts of interest that arise when advisory personnel trade for their own accounts. A key component of the code of ethics is the requirement for access persons to report their personal securities transactions and holdings. An access person generally includes any supervised person who has access to nonpublic information regarding client transactions or portfolio holdings, or who is involved in making securities recommendations to clients. The rule mandates that access persons submit quarterly transaction reports, typically within 30 days of the end of each calendar quarter. These reports must detail all personal securities transactions during that period. While the rule itself explicitly requires pre-clearance only for investments in initial public offerings (IPOs) and limited offerings, it also obligates the adviser’s code of ethics to establish procedures for managing personal trading. In practice, to manage the conflict of interest when an access person trades a security that the firm is also recommending to clients, most firms implement a mandatory pre-clearance policy for all or a significant subset of personal trades. This is considered a best practice and is the primary mechanism by which a firm ensures that client interests are placed first. Therefore, the access person’s immediate responsibility is to adhere to the firm’s specific procedures outlined in its code of ethics, which almost certainly includes a pre-clearance requirement for this type of transaction. Following this internal procedure is the first step before the subsequent regulatory requirement of reporting the transaction on the quarterly report.

-

Question 17 of 30

17. Question

Anika is an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) at Pinnacle Wealth Managers, a federal covered adviser. She decides to invest in a speculative real estate limited partnership. Believing it falls outside her firm’s compliance purview because Pinnacle does not recommend or analyze limited partnerships, she opens a new brokerage account at an unaffiliated firm to make the purchase. She does not inform her Chief Compliance Officer (CCO) about the new account or the transaction. Three months later, the CCO discovers the account during a periodic compliance review. Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, which statement most accurately describes Anika’s regulatory failure?

Correct

Logical Deduction of Violation: 1. Applicable Regulation: The conduct of an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) at a federal covered adviser concerning personal securities trading is governed by the firm’s Code of Ethics, which is mandated by Rule 204A-1 under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. 2. Individual’s Status: Anika, as an IAR, is considered an “access person” because she has access to nonpublic information regarding clients’ securities transactions and portfolio holdings, and is involved in making securities recommendations. 3. Regulatory Requirement: Rule 204A-1 requires that a firm’s Code of Ethics must, at a minimum, require access persons to report their personal securities holdings and transactions. A key component of this is the monitoring of outside accounts. To facilitate this, the rule requires access persons to report, and most firm procedures mandate they obtain approval for, any new securities account established with another broker-dealer or financial institution. 4. Action Analysis: Anika established a new securities account at an external firm without notifying her employer. 5. Conclusion: The failure to provide prior written notification and receive approval for opening a new securities account is a direct violation of the requirements stipulated under Rule 204A-1. The fact that the investment was in an asset class not typically recommended by the firm does not negate this fundamental reporting obligation, which is designed to give the firm oversight of all potential conflicts of interest. Rule 204A-1 of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 requires registered investment advisers to adopt and enforce a code of ethics. This code is designed to prevent fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative practices. A central element of this rule applies to “access persons,” which typically includes all supervised persons who have access to nonpublic information regarding client transactions or portfolio holdings or who are involved in making recommendations to clients. As an IAR, an individual falls squarely within this definition. The rule mandates that access persons must report their personal securities holdings and transactions to the firm’s Chief Compliance Officer (CCO) or another designated person. This includes an initial holdings report upon becoming an access person, annual holdings reports thereafter, and quarterly transaction reports. Crucially, to ensure comprehensive oversight, access persons are also required to report any new accounts they open through which securities can be traded. Many firms, to comply with the spirit and letter of the rule, require pre-clearance or at least prior written notification before an access person opens such an account. The belief that an investment is outside the firm’s usual scope of recommendations is not a valid reason to bypass this requirement, as the rule is intended to provide the firm with a complete picture of an access person’s activities to monitor for any potential conflicts of interest or misuse of information.

Incorrect

Logical Deduction of Violation: 1. Applicable Regulation: The conduct of an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) at a federal covered adviser concerning personal securities trading is governed by the firm’s Code of Ethics, which is mandated by Rule 204A-1 under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. 2. Individual’s Status: Anika, as an IAR, is considered an “access person” because she has access to nonpublic information regarding clients’ securities transactions and portfolio holdings, and is involved in making securities recommendations. 3. Regulatory Requirement: Rule 204A-1 requires that a firm’s Code of Ethics must, at a minimum, require access persons to report their personal securities holdings and transactions. A key component of this is the monitoring of outside accounts. To facilitate this, the rule requires access persons to report, and most firm procedures mandate they obtain approval for, any new securities account established with another broker-dealer or financial institution. 4. Action Analysis: Anika established a new securities account at an external firm without notifying her employer. 5. Conclusion: The failure to provide prior written notification and receive approval for opening a new securities account is a direct violation of the requirements stipulated under Rule 204A-1. The fact that the investment was in an asset class not typically recommended by the firm does not negate this fundamental reporting obligation, which is designed to give the firm oversight of all potential conflicts of interest. Rule 204A-1 of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 requires registered investment advisers to adopt and enforce a code of ethics. This code is designed to prevent fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative practices. A central element of this rule applies to “access persons,” which typically includes all supervised persons who have access to nonpublic information regarding client transactions or portfolio holdings or who are involved in making recommendations to clients. As an IAR, an individual falls squarely within this definition. The rule mandates that access persons must report their personal securities holdings and transactions to the firm’s Chief Compliance Officer (CCO) or another designated person. This includes an initial holdings report upon becoming an access person, annual holdings reports thereafter, and quarterly transaction reports. Crucially, to ensure comprehensive oversight, access persons are also required to report any new accounts they open through which securities can be traded. Many firms, to comply with the spirit and letter of the rule, require pre-clearance or at least prior written notification before an access person opens such an account. The belief that an investment is outside the firm’s usual scope of recommendations is not a valid reason to bypass this requirement, as the rule is intended to provide the firm with a complete picture of an access person’s activities to monitor for any potential conflicts of interest or misuse of information.

-

Question 18 of 30

18. Question

The following case study involves Kenji, an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR). Kenji has a close friend who is a mid-level software engineer at Innovatech Corp., a publicly traded company. During a private dinner, the friend expresses extreme frustration over a catastrophic failure in a key component for Innovatech’s upcoming flagship product, stating that the launch will be delayed by at least two quarters. This information is not yet known to the public. The next day, Kenji sells his entire personal position in Innovatech stock. In accordance with his firm’s policies and the Investment Advisers Act, he includes this transaction on his next required quarterly personal transaction report. Which statement most accurately assesses Kenji’s conduct?

Correct